MONTPELIER — Ninety years to the day a bill legalizing sterilization targeting Abenaki people, French Canadian and French Indian immigrants, the poor and the mentally ill was signed into law, the Vermont House of Representatives confronted the grim history of the state's eugenics movement and unanimously endorsed a resolution apologizing for its actions nearly a century ago.

In the resolution, the General Assembly “sincerely apologizes and expresses its sorrow and regret to all individual Vermonters and their families and descendants who were harmed as a result of State-sanctioned eugenics policies and practices.”

It further “recognizes that further legislative action should be taken to address the continuing impact of State-sanctioned eugenics policies and related practices of disenfranchisement, ethnocide, and genocide.”

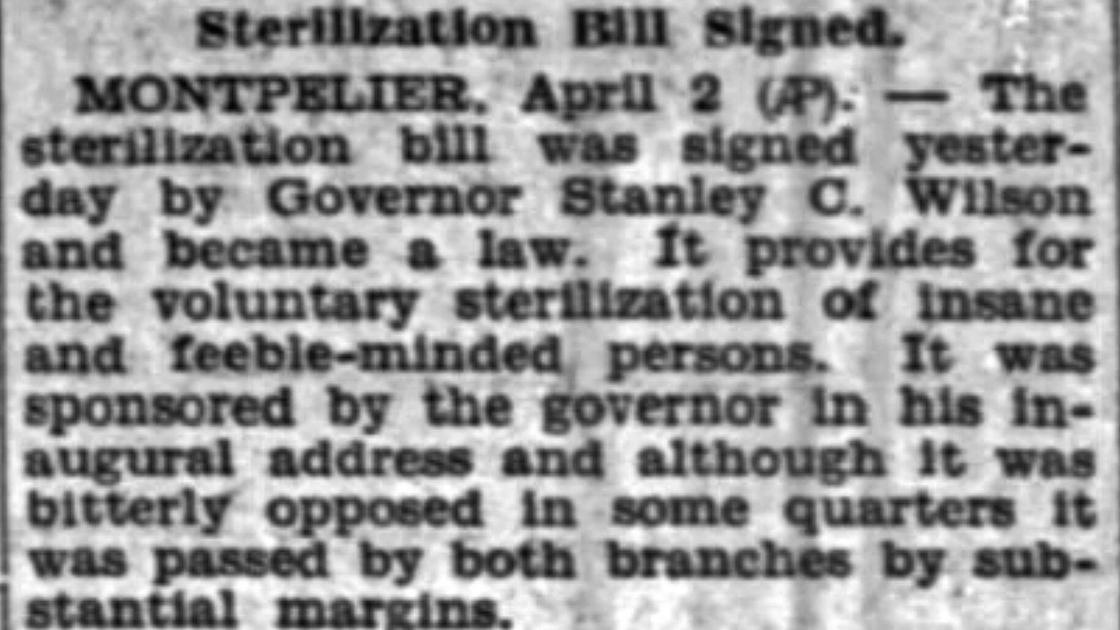

The apology centers on Act 174, a bill passed by the Legislature in 1931 allowing for voluntary sterilizations. But in a lengthy presentation to the House, Rep. Thomas Stevens, D-Washington-Chittenden, offered a thorough history lesson showing that eugenics, and policies that targeted people labeled as "degenerate," "defective" and "feeble-minded," reached back to the turn of the 20th century, and that the General Assembly had set the stage for Act 174 well in advance of its passage.

"We acknowledge that these policies of separation, institutionalization and sterilization were driven by social and ideological imperatives, based on racial, ethnic, class and gender biases and prejudice," Stevens said. "By apologizing now, we are saying that policies we undertake in the future, including many bills that we have considered already this session, will be considered in the spirit of correcting those harms."

"Finally, we are acknowledging what we as an institution had historically done while recognizing that while we are not personally responsible, our institution bears responsibility," Stevens said.

The resolution passed unanimously on a roll call vote, 146-0. It now heads to third reading, and to the Senate upon passage.

The passage culminates years of effort, starting with an initiative 12 years ago by Rep. Anne B. Donahue, R-Washington 1. Donahue, speaking in favor of passage, said the apology serves as a reminder to the General Assembly to have "the humility to recognize we can err."

"No one in Vermont in 1931 sat in our seats and said 'I want to do something wrong,'" Donahue said. "We need to avoid the hubris of thinking we are immune, today, to making decisions hindsight will not expose."

A GRIM HISTORY

The eugenics movement put forth that by limiting reproduction among the afflicted -- who happened to be Abenaki, French first peoples Canadians, and people of color -- the population would limit “feeble-mindedness” and promote the "good old Vermont stock."

The theory found an audience in the Vermont General Assembly. While the Legislature had written and passed related legislation earlier, in March of 1931 it approved what became Act 174: “An act for human betterment by voluntary sterilization.”

The first section read as follows: “Henceforth it shall be the policy of the state to prevent procreation of idiots, imbeciles, feebleminded or insane persons, when the public welfare, and the welfare of idiots, imbeciles, feeble‐minded or insane persons likely to procreate, can be improved by voluntary sterilization as herein provided.”

More than 250 persons were sterilized in Vermont between 1931 and the mid-20th century, though the complete number may never be known, Stevens said. A majority were women, he said.

Stevens, of Waterbury, offered a thorough history lesson showing that the eugenics movement in Vermont had roots running far deeper than University of Vermont professor Henry Perkins, and far earlier than the 1920s, when Perkins began efforts leading to the 1931 law.

The first mention of eugenics as a solution to caring for the poor and mentally ill in Vermont, Stevens said, came from Gov. John Mead in 1912. In his farewell address to the Legislature, Mead called for marriage restrictions, segregation and sterilization as a means to control the population of "defectives."

That led to the House considering, and sometimes passing, bills that carried out eugenics-related policies, such as the establishment of the state school for "feeble-minded" children in Brandon in 1912, and the child welfare act of 1915, which defined neglected and delinquent children by law and led to increases in children being separated from their families and institutionalized.

A bill that would have allowed for sterilization was passed by both houses of the Legislature in 1913, but vetoed by Gov. Allen Fletcher as unconstitutional.

PERSONAL STORIES

Stevens said the resolution was made stronger by people who came forward with family stories of how the eugenics movement hurt them and their families. He said witnesses described how they hid their ancestry to avoid persecution, changing their names and denying their heritage, and learned to mistrust government.

"We labelled people with words like 'feeble-minded,' 'imbecile,' 'idiot,' 'pirate,' 'basketweaver' and 'gypsy,' and by labelling them, we negated them," Stevens said. "We dehumanized them and made them less than, which, we know from what we heard, was internalized and further compounded the pain over decades of time."

Research and testimony showed another common thread to the targets of eugenics, Stevens said: Poverty. "We while know we’ve made some progress, and some amends, the prejudice and pain our policies cultivated continues," he said.

For many members of the House, the vote was personal.

Rep. Hal Colston, D-Chittenden 6-7, said as a black man, he experiences much of the same fear and stress that the survivors of the eugenics movement experienced.

"Excess death is experienced by black people every day," Colston said, as the stress of racism leads to a constant state of 'fight or fight' response.

In my view this is slow-motion genocide. ... We must face the truth of our state's history."

Rep. Emilie Kornheiser, D-Windham 2-1, said the Holocaust affected her family directly, and hopes the apology rebuilds trust in communities that were injured by state policy.

I am hopeful this apology in this moment, which is so deeply felt by so many of our members, can be a starting point in healing," Kornheiser said.

And Rep. Tommy Walz, D-Washington-3, said as a German-American for whom the Holocaust has always been a dark cloud over his heritage, said Vermont should confront its past, as post-World War II Germany did.

"We cannot right the wrongs of the past. We cannot bring back the lives lost or never born. We can do the right thing. We can take ownership. We can acknowledge the wrong and our part in it."

Rep. Janet Ancel, D-Washington 6, said as a young social worker, she met a woman at the Waterbury State Hospital who was sterilized.

"I remember her name. I can picture her today, Ancel said. "I remember her diagnosis; she certainly wasn't mentally ill. And I remember the day she told me about the operation. When I cast my yes vote today it will be in her honor and in her memory."

State Rep Barbara Murphy, I-Franklin-2, said her grandfather, Sen. Levi P. Smith, represented the Chittenden district in 1927 and voted for a sterilization bill that passed the Senate but failed in the House.

"I feel privileged to have had the opportunity to be part of the work done on this resolution, said Murphy, of Fairfax. "My family history will now include my vote today."

In 2019, the University of Vermont apologized for "stereotyping, persecution and in some cases state sponsored sterilization.” The university also removed the name of former university president Guy Bailey, who supported Perkins’ work, from its library.

"in" - Google News

April 01, 2021 at 07:15AM

https://ift.tt/3fsZLfj

Vermont House unanimously apologizes for its role in eugenics policies - Bennington Banner

"in" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2MLa3Y1

https://ift.tt/2YrnuUx

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Vermont House unanimously apologizes for its role in eugenics policies - Bennington Banner"

Post a Comment